Or, how Microsoft may have just invented the future of intensive Bible study.

Microsoft this week unveiled HoloLens, an augmented-reality headset that overlays text and images on the real world and, in particular, anchors them to precise locations in space, as if they were real objects. Here’s one of Microsoft’s promotional shots to give you an idea of what wearing HoloLens is like:

In this image, the man is apparently so obsessed with going to Maui that he maintains a Sims-like vacation paradise on his counter. The TV, “Recipes” button, Maui simulation, and to-do list are all virtual—using the device on his head, only he can see whether his Sims manage find a staircase to the beach or if instead they simply leap the fifteen feet off the cliff to the sand.

At this year’s BibleTech conference, I’m going to discuss why the idea of the “digital library” doesn’t appeal to certain kinds of people, and one aspect of the discussion involves the tension between print books and digital ones, each of which has advantages and disadvantages. Microsoft’s holographic technology (I recognize that one, they’re not really holograms, and two, what I’m describing here may go beyond what’s possible in the first devices) presents an intriguing way to bridge the physical and digital worlds of Bible study.

Certain kinds of people prefer to study from print Bibles, and for them digital resources serve as study augmentations: parallel Bibles and commentaries feature prominently in this kind of study practice. The melding of physical and digital has always been awkward for this type of person, although tablet computers have eased this awkwardness somewhat. Still, the main limitation of digital resources for this person is space; small screens (compared to the size of a desk) don’t provide enough room to look at very many resources simultaneously, forcing them to toggle between resources. Edward Tufte calls this phenomenon being “stacked in time” rather than “adjacent in space,” saying that the latter is generally preferable.

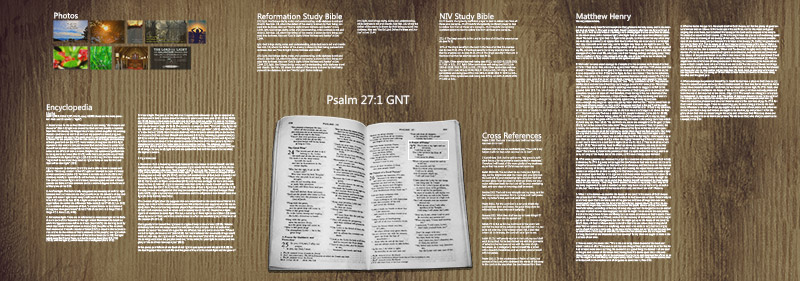

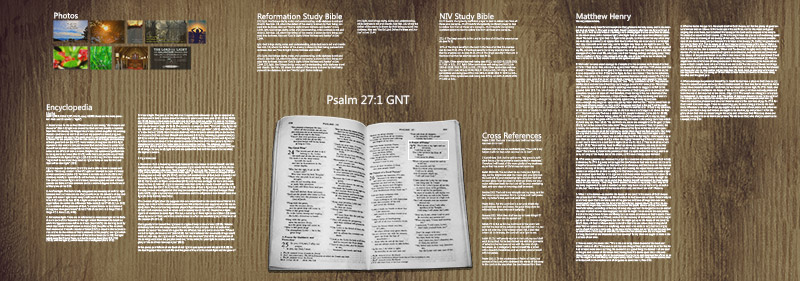

Holograms remove this space limitation by expanding your working area to your entire physical desktop:

In this image, only the physical Bible and the desk are actually there. The rest of the text appears to float on top of the desk, providing enough room to engage in the kind of deep study that you might crave. Here I imagine that you, wearing holographic goggles, have tapped Psalm 27:1 in your print Bible. The goggles recognize the gesture, draw a box around the text in your Bible, and provide all sorts of supplementary material in which you’ve previously expressed interest: photos for some sort of illustration, various commentary and exegetical helps, and cross-references. The digital resources displayed on the desk are interactive, letting you tap and scroll much as you would on a tablet computer. It’s a tablet without a tablet.

Of course, if you have a whole lot of material, there’s no need to limit supplementary material to a desktop; the whole room is available to you:

This image limits content to walls, but Microsoft’s HoloLens demo shows that the content could just as easily exist as three-dimensional objects in the middle of the room. And while I focus on low-density information displays here, there could easily be hundreds of information cards. Do you want to conduct a keyword search with hundreds of results? You can see all of them at once, all around you, rather than paging through them a few at a time.

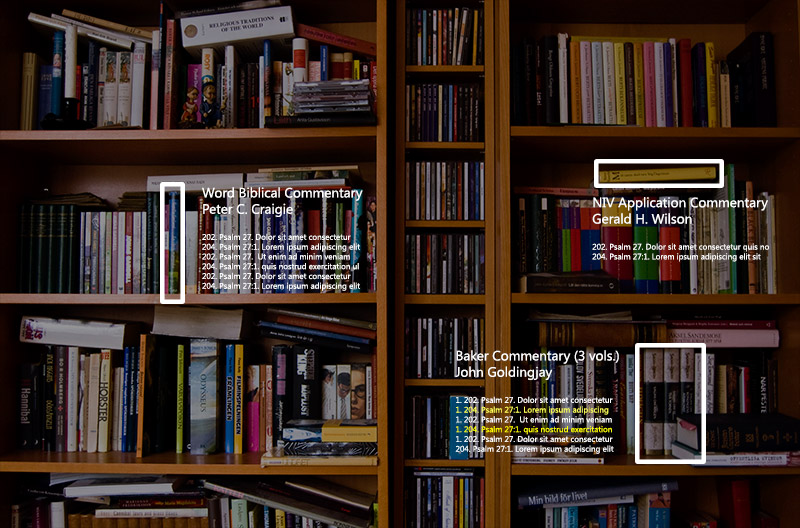

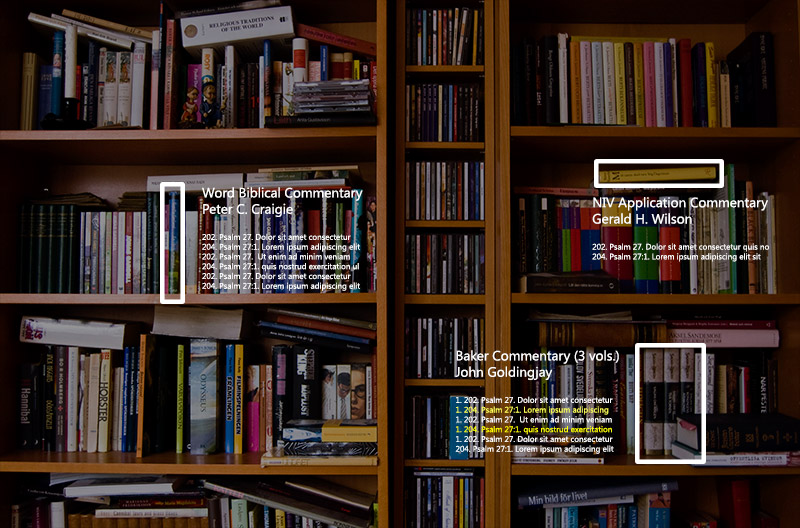

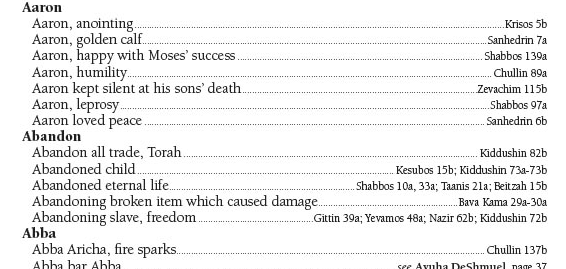

Further, holograms give you the opportunity to merge print and digital resources in new ways. Suppose you’re studying Psalm 27:1, as above, and vaguely remember something you read once in one of your books. If you look over at your bookshelves, you might see something like this:

Here the holographic goggles have identified relevant books for you and show you where they are on your bookshelves, in addition to providing relevant excerpts for you to peruse. (The goggles know the page numbers either because you own the same volume digitally or because you originally read the book with your goggles on, and the goggles remember everything you read, even if you don’t; it’s like a super-Evernote.) The goggles surface passages related to the verse you’re reading and even remember passages you’ve highlighted (the yellow lines in the image). You can interact further with the holograms, looking through more search results, perhaps, or you can pull one of the books off the shelf and physically peruse it.

Finally, and most obviously, holograms push the 3D models, timelines, and maps that are now study-Bible staples into new dimensions of interactivity. They can literally pop off the page and expand into space, letting you manipulate them in ways that are impossible in the 2D space of a screen.

Holographic technology neatly sidesteps several limitations of current digital Bible study and could potentially usher widespread, transformative, digitally assisted Bible study. Or they may be just too geeky-looking. We’ll have to see.

Photo credits: endyk, Hc_07, 4thglryofgod, worshipbackgrounds, listentothemountains, coloneljohnbritt, 4thglryofgod, titobalangue, quoteseverlasting, steven_jamesP, nlcwood, netzanette, and williamhook on Flickr. The terrible Photoshopping is all my fault, not theirs.

After all, from a data perspective, sermons don’t differ much from sports stories. In particular, they have three components:

After all, from a data perspective, sermons don’t differ much from sports stories. In particular, they have three components:

In Redmond, Wash., a start-up called 3D Outlook Corp. this month will begin using software from NASA to sell 3-D models of mountains and other terrain priced at under $100, says Tom Gaskins, the company’s chief executive officer. Mr. Gaskins says hikers, resorts and real-estate firms are likely customers for 3-D maps and models that show the topographic contours of ski slopes, golf courses and other landscapes.

In Redmond, Wash., a start-up called 3D Outlook Corp. this month will begin using software from NASA to sell 3-D models of mountains and other terrain priced at under $100, says Tom Gaskins, the company’s chief executive officer. Mr. Gaskins says hikers, resorts and real-estate firms are likely customers for 3-D maps and models that show the topographic contours of ski slopes, golf courses and other landscapes.