Here are the slides from a talk I gave today at the BibleTech conference in Seattle. Download the accompanying handout or explore the Expanded Bible interface mentioned in the presentation.

Archive for the ‘Collective Intelligence’ Category

Designing for Agency in Bible Study

Saturday, April 13th, 2019How to Train Your Franken-Bible

Saturday, March 16th, 2013This is the outline of a talk that I gave earlier today at the BibleTech 2013 conference.

- There are two parts to this talk

- Inevitability of algorithmic translations. An algorithmic translation (or “Franken-Bible”) means a translation that’s at least partly done by a computer.

- How to produce one with current technology.

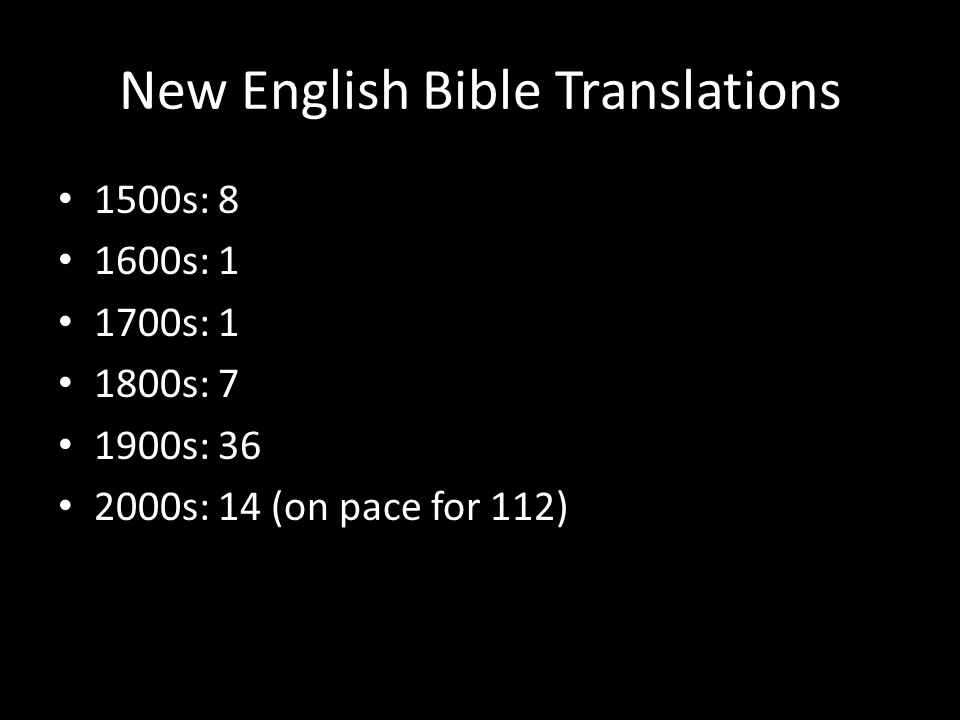

- The number of English translations has grown over the past five centuries and has accelerated recently. This growth mirrors overall trend in publishing as costs have diminished and publishers have proliferated.

- I argue that this trend of ever-more translations will not only continue but will accelerate, that we’re heading for a post-translation world, where the number of English translations becomes so high, and the market so fragmented, that Bible translations as distinct identities will have much less meaning than they do today.

- This trend isn’t specific to Bibles, but Bible translations participate in the larger shift to more diverse and fragmented cultural expressions.

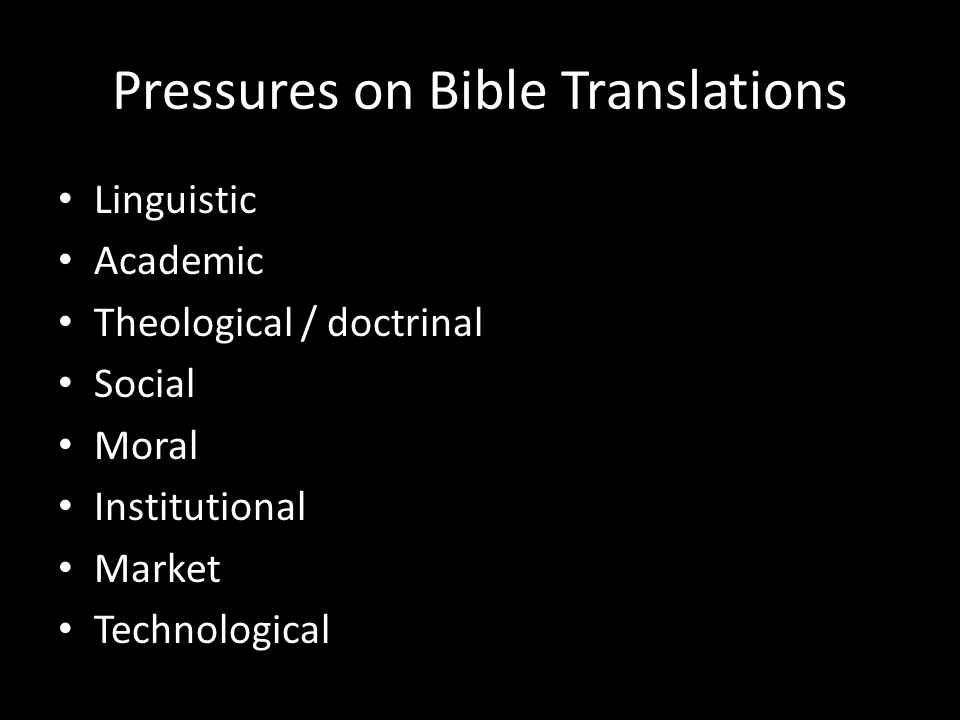

- Like other media, Bible translations are subject to a variety of pressures.

- Linguistic (e.g., as English becomes more gender-inclusive, pressure rises on Bible translations to also become more inclusive).

- Academic (discoveries that shed new light on existing translations). My favorite example is Matthew 17:15, where some older translations say, “My son is a lunatic,” while newer translations say, “My son has epilepsy.”

- Theological / doctrinal (conform to certain understandings or agendas).

- Social (decline in public religious influence leads to a loss of both shared stories and religious vocabulary).

- Moral (pressure to address whatever the pressing issue of the day is).

- Institutional (internally, where Bible translators want control over their translations; and externally, with the wider, increasing distrust of institutions).

- Market. Bible translators need to make enough money (directly or indirectly) to sustain translation operations.

- Technological. Technological pressure increases the variability and intensity of other pressures and is the main one we’ll be investigating today.

- If you’re familiar with Clayton Christensen’s The Innovator’s Dilemma, you know that the basic premise is that existing dominant companies are eventually eclipsed by newer companies who release an inferior product at low prices. The dominant companies are happy to let the new company operate in this low-margin area, since they prefer to focus on their higher-margin businesses. The new company then steadily encroaches on the territory previously staked out by the existing companies until the existing companies have a much-diminished business. Eventually the formerly upstart company becomes the incumbent, and the cycle begins again.

- One of the main drivers of this disruption is technology, where a technology that’s vastly inferior to existing methods in terms of quality comes at a much lower price and eventually supersedes existing methods.

- I argue that English Bible translation is ripe for disruption, and that this disruption will take the form of large numbers of specialized translations that are, from the point of view of Bible translators, vastly inferior. But they’ll be prolific and easy to produce and will eventually supplant existing modern translations.

- For an analogy, let’s look at book publishing (or any media, really, like news, music, or movies. But book publishing is what I’m most familiar with, so it’s what I’ll talk about). In the past twenty years, it’s gone through two major disruptions.

- The first is a disruption in distribution, with Amazon.com and other web retailers. National bookstore chains consolidated or folded as they struggled to figure out how to compete with the lower prices and wider selection offered online.

- This change hurt existing retailers but didn’t really affect the way that content creators like publishers and authors did business. From their perspective, selling through Amazon isn’t that different from selling through Barnes & Noble.

- The second change is more disruptive to content creators: this change is the switch away from print books to ebooks. At first, this change seems more like a difference in degree rather than in kind. Again, from a publisher’s perspective, it seems like selling an ebook through Amazon is just a more-convenient way of selling a print book through Amazon.

- But ebooks actually allow whole new businesses to emerge.

- I’d argue that these are the main functions that publishers serve for authors–in other words, why would I, as an author, want a publisher to publish my book in exchange for some small cut of the profit?

- Gatekeeping (by publishing a book, they’re saying it’s worth your time and has a certain level of quality: it’s been edited and vetted).

- Marketing (making sure that people know about and buy books that are interesting to them).

- Distribution (historically, shipping print books to bookstores).

- Ebooks most-obviously remove the distribution pillar of this model–when producing and distributing an epub only involves a few clicks, it’s hard to argue that a publisher is adding a whole lot of value in distribution.

- That leaves gatekeeping and marketing, which I’ll return to later in the context of Bibles.

- But beyond just affecting these pillars, ebooks also allow new kinds of products:

- First, a wider variety of content becomes more economically viable–content that’s too long or too short to print as a book can work great as an ebook, for example.

- Second, self-publishing becomes more attractive: when traditional publishing shuns you because, say, your book is terrible, just go direct and let the market decide just how terrible it is. And if no one will buy it, you can always give it away–it’s not like it’s costing you anything.

- So ebooks primarily allow large numbers of low-quality, low-priced books into the market, which fits the definition of disruption we talked about earlier.

- Let’s talk specifically about Bible translations.

- Traditionally, Bible translations have been expensive endeavors, involving teams of dozens of people working over several years.

- The result is a high-quality product that conforms to the translation’s intended purpose.

- In return for this high level of quality, Bible publishers charge money to, at a minimum, recoup their costs.

- What would happen if we applied the lessons from the ongoing disruption in book publishing to Bible translations?

- First, like Amazon and physical bookstores, we disrupt distribution.

- Bible Gateway in 1993 on the web first disrupted distribution by letting people browse translations for free.

- YouVersion in 2010 on mobile then took that disruption a step further by letting people download and own translations for free.

- But we’re really only talking about a disruption in distribution here. Just like with print books, this type of disruption doesn’t affect the core Bible-translation process.

- That second type of disruption is still to come and will eventually arrive; I’m going to argue that, as with ebooks, the disruption to translations themselves will be largely technological and will result in an explosion of new translations.

- I believe that this disruption will take the form of partially algorithmic personalized Bible translations, or Franken-Bibles.

- Because Bible translation is a specialized skill, these Franken-Bibles won’t arise from scratch–instead, they’ll build on existing translations and will be tailored to a particular audience–either a single individual or a group of people.

- In its simplest form, a Franken-Bible could involve swapping out a footnote reading for the reading that’s in the main text.

- A typical Bible has around 1100 footnotes indicating alternate translations. What if a translation allowed you to decide which reading you preferred–either by setting a policy (for example, you might, say, “always translate adelphoi in a particular way”) or by deciding on a case-by-case basis.

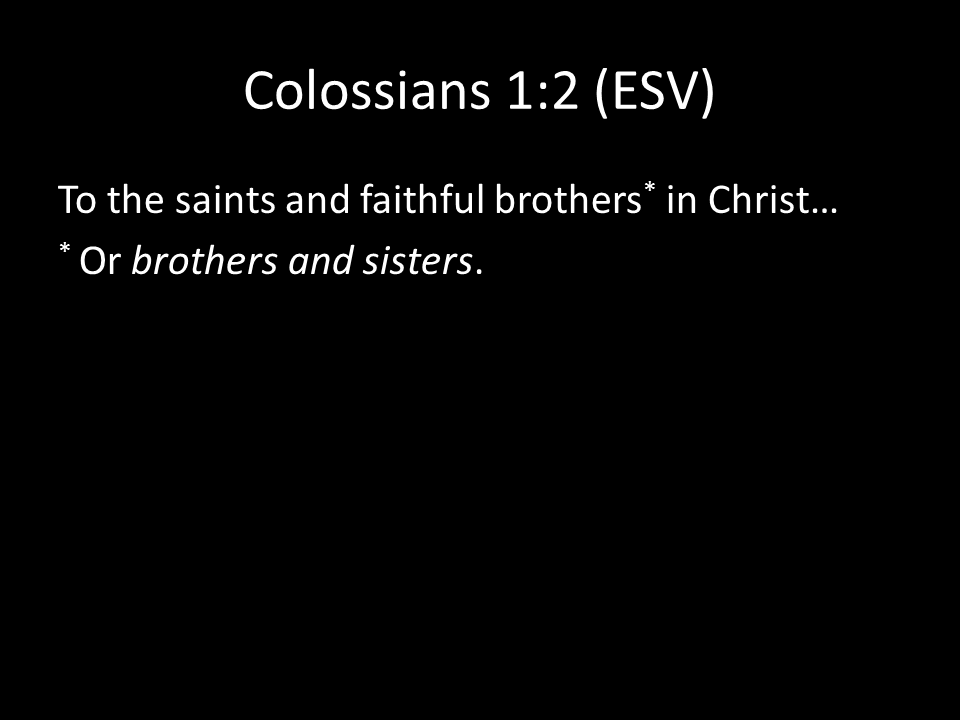

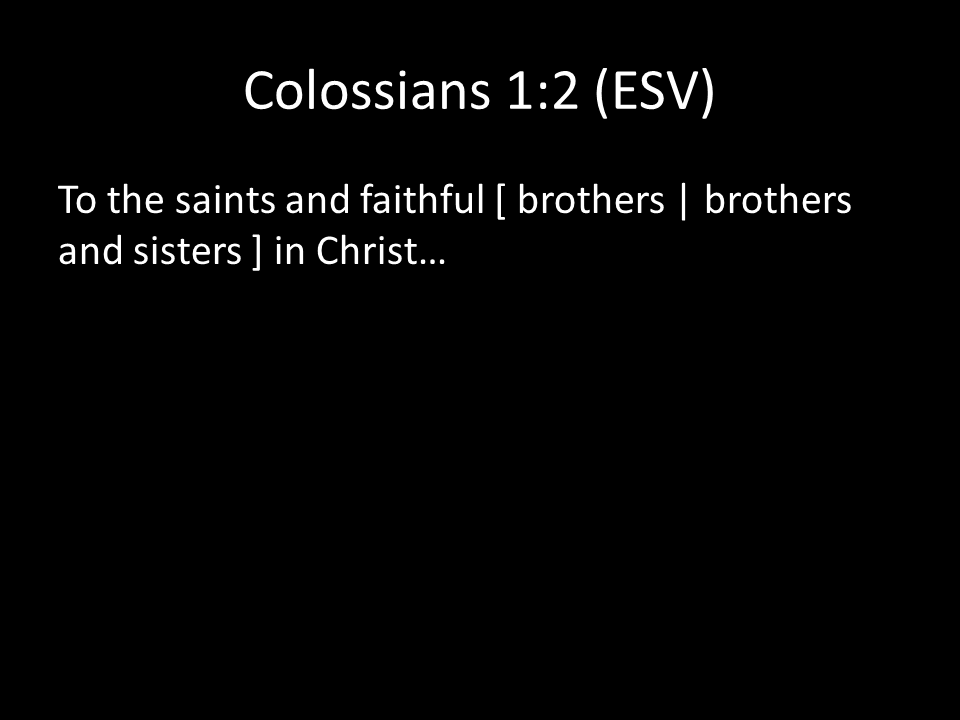

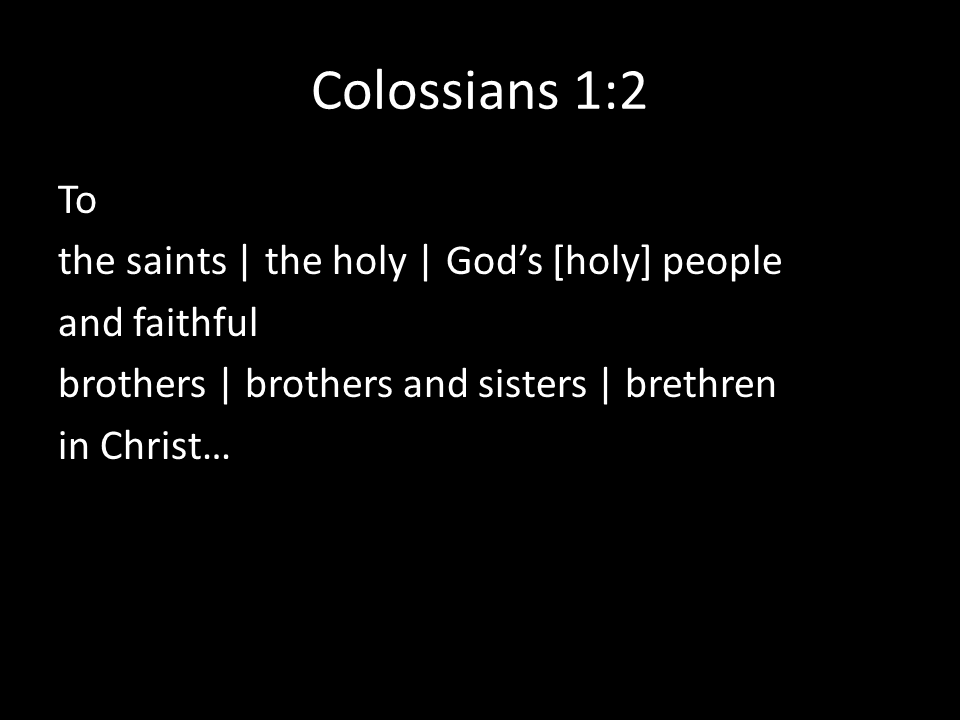

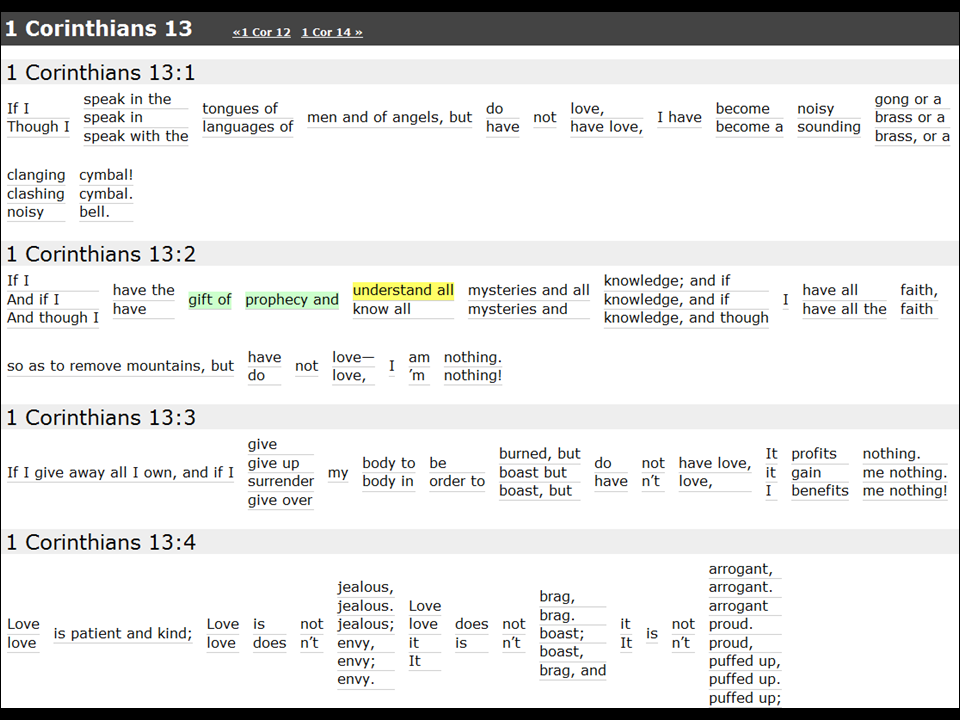

- By including footnote variants at all, translations have already set themselves up for this approach. Some translations go even further–the Amplified and Expanded Bibles embrace variants by embedding them right in the text. Here we see a more-extensive version of the same idea.

- But that’s the simplest approach. A more-radical approach, from a translation-integrity perspective, would allow people to edit the text of the translation itself, not merely to choose among pre-approved alternatives at given points.

- In many ways, the pastor who says in a sermon, “This verse might better be translated as…” is already doing this; it just isn’t propagated back into the translation.

- People also do this on Twitter all the time, where they alter a few words in a verse to make it more meaningful to them.

- The risk here, of course, is that people will twist the text beyond all recognition, either through incompetence or malice.

- That risk brings us back to one of the other two functions that publishers serve: gatekeeping.

- A translation is nothing if not gatekeeping: a group of people have gotten together and declared, “This is what Scripture says. These are our translation principles, and here’s where we stand in relation to other translations.”

- What happens to gatekeeping–to the seal of authority and trust–when anyone can change the text to suit themselves?

- In other words, what happens if the “Word of God” becomes the “Wiki of God?”

- After all, people who aren’t interested in translating their own Bible still want to be able to trust that they’re reading an accurate, or at least non-heretical, translation.

- I suggest that new axes of trust will form. Whereas today a translation “brand”–NIV, ESV, or whatever–carries certain trust signals, those signals will shift to new parties, and in particular to groups that people already trust.

- The question of whom you’d trust to steward a Bible translation probably isn’t that different from whomever you already trust theologically, a group that probably includes some of the following:

- Social network.

- Teachers or elders in your church.

- Pastors in your church.

- Your denomination.

- More indirectly, a megachurch pastor you trust.

- A parachurch organization or other nonprofit.

- Maybe even a corporation.

- The point is not that trust in a given translation would go away, but rather that trust would become more networked, complicated, and fragmented, before eventually solidifying.

- We already see this happening somewhat with existing Bible translations, where certain groups declare some translations as OK and others as questionable. Like your choice of cellphone, the translation you use becomes an indicator of group identity.

- The proliferation of translations will allow these groups who are already issuing imprimaturs to go a step further and advance whole translations that fit their viewpoints.

- In other words, they’ll be able to act as their own Magisteriums. Their own self-published Magisteriums.

- This, by the way, also addresses the third function that publishers serve: marketing. By associating a translation with a group you already identify with, you reduce the need for marketing.

- The question of whom you’d trust to steward a Bible translation probably isn’t that different from whomever you already trust theologically, a group that probably includes some of the following:

- I said earlier that I think technology will bring about this situation, but there are a couple ways it could happen.

- First, an existing modern translation could open itself up to such modifications. A church could say, “I like this translation except for these ten verses.” Or, “This translation is fine except that it should translate this Greek word this way instead of this other way.”

- Such a flexible translation could provide the tools to edit itself–with enough usage, it’s possible that useful improvements could be incorporated back into the original translation.

- A second alternative is to use technology to produce a new, cheap, low-quality translation with editing in mind from the get-go, to provide a base from which a monstrous hydra of translations can grow. Let’s take a look at what such a hydra translation, or a Franken-Bible, could look like.

- The basic premise is this: there are around thirty modern, high-quality translations of the Bible into English. Can we combine these translations algorithmically into something that charts the possibility space of the original text?

- Bible translators already consult existing translations to explore nuances of meaning. What I propose is to consult these translations computationally and lay bare as many nuances as possible.

- You can explore the output of what I’m about to discuss at www.adaptivebible.com. I’m going to talk about the process that went into creating the site.

- This part of the talk is pretty technical.

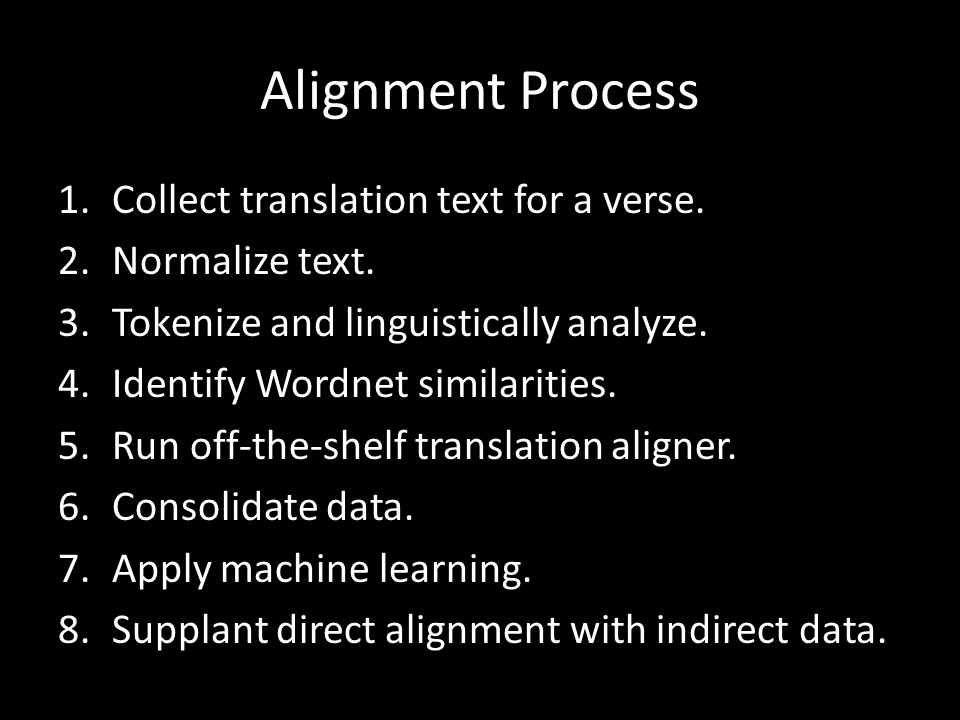

- In all, there are fifteen steps, broken into two phases: alignment of existing translations and generation of a new translation.

- It took about ten minutes of processor time for each verse to produce the result.

- The total cost in server time on Amazon EC2 to translate the New Testament was about $10. Compared to the millions of dollars that a traditional translation costs, that’s a big savings–five or six orders of magnitude.

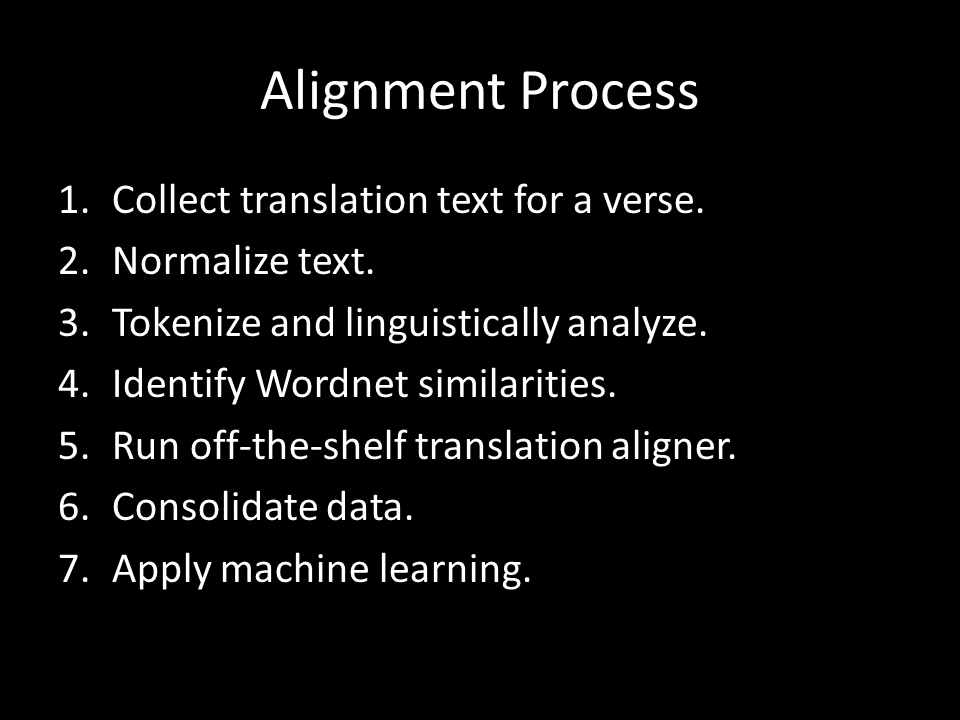

- The first phase is alignment.

- First step. Collect as many English translations as possible. Obviously there are copyright implications with doing that, so it’s important to deal with only one verse at a time, which is something that all translations explicitly allow. For this project, we used around thirty translations.

- Second. Normalize the text as much as possible. For this project, we’re not interested in any formatting, for example, so we can deal with just the plain text.

- Third. Tokenize the text and run basic linguistic analysis on it.

- Off-the-shelf open-source software from Stanford called Stanford CoreNLP tokenizes the text, identifies lemmas (base forms of words) and analyzes how words are related to each other syntactically.

- In general, it’s about 90% accurate, which is fine for our purposes; we’ll be trying to enhance that accuracy later.

- Fourth. Identify Wordnet similarities between translations.

- Wordnet is a giant database of word meanings that computers can understand.

- We take the lemmas from the step 3 and identify how close in meaning they are to each other. The thinking is that even when translations use different words for the same underlying Greek word, the words they choose will at least be similar in meaning.

- For this step, we used Python’s Natural Language Toolkit.

- Fifth. Run an off-the-shelf translation aligner.

- We used another open-source program called the Berkeley Aligner, which is designed to use statistics to align content between different languages. But it works just as well for different translations of the same content in the same language. It takes anywhere from two to ten minutes for each verse to run.

- Sixth. Consolidate all this data for future processing.

- By this point, we have around 4MB of data for each verse, so we consolidate it into a format that’s easy for us to access in later steps.

- Seventh. Run a machine-learning algorithm over the data to identify the best alignment between single words in each pair of translations.

- We used another Python module, scikit-learn, to execute the algorithm.

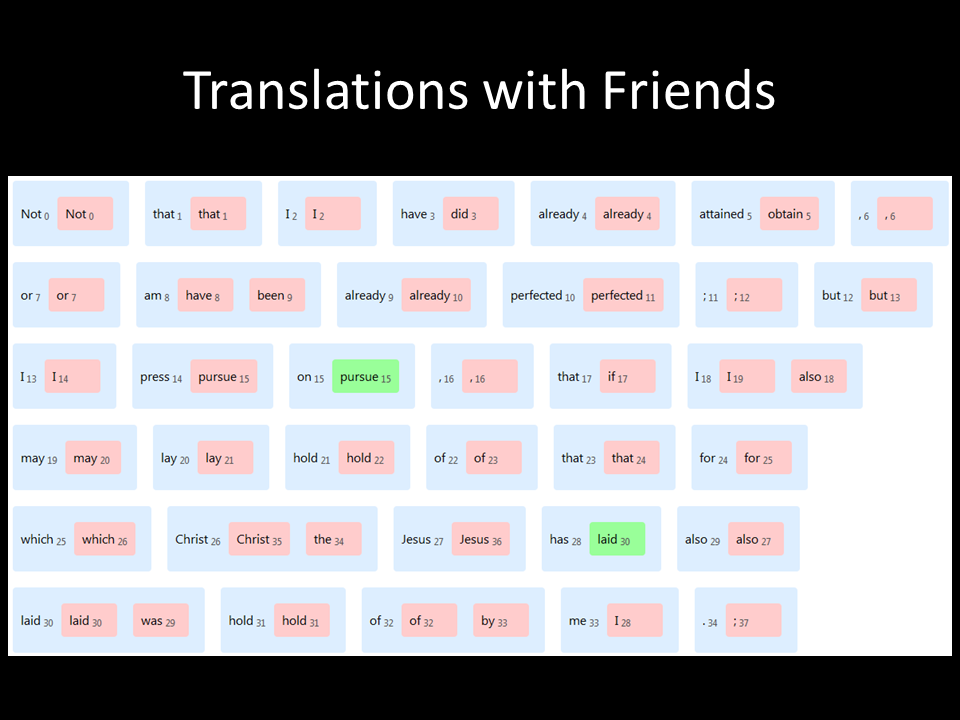

- In particular, we used Random Forest, which is a supervised-learning system. That means we need to feed it some data we know is good so that it can learn the patterns in the data.

- Where did we get this good data? We wrote a simple drag-and-drop aligner to feed the algorithm, where there are two lists of words and you drag them on top of each other if they match; it’s actually kind of fun: if you juiced it up a little, I can totally see it becoming a game called “Translations with Friends.”

- In total, we hand-aligned around 30 pairs of translations across 25 verses. There are about 8,000 verses in the New Testament, so it doesn’t need a lot of training to get good results.

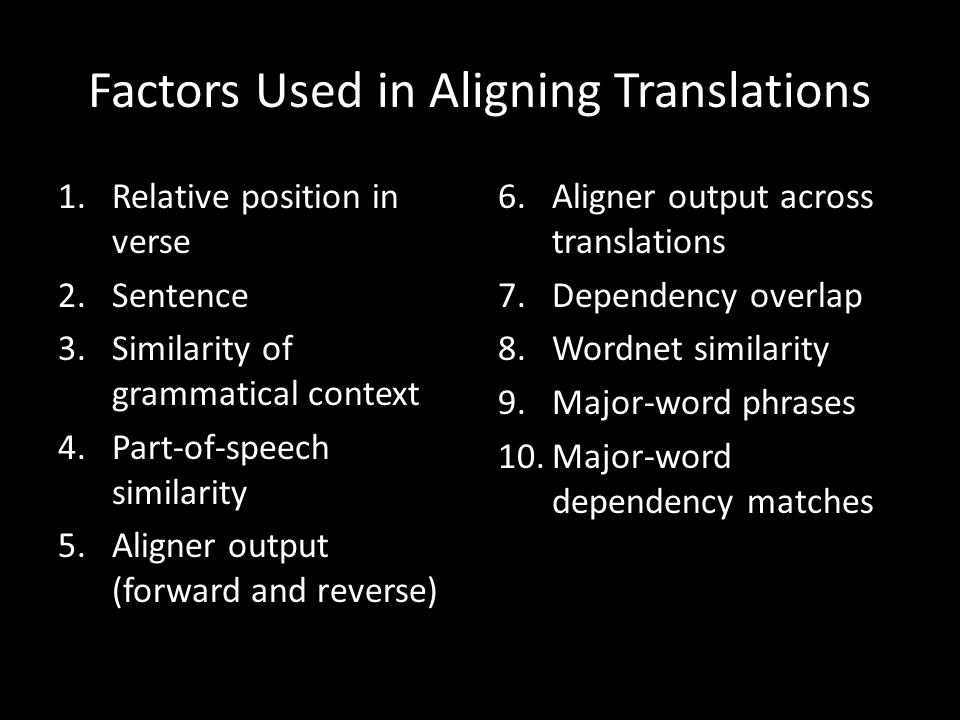

- What the algorithm actually runs on is a big vector matrix. These are the ten factors we included in our matrix.

- 1. One translation might begin a verse with the words “Jesus said,” while another might put that same phrase at the end of the verse. All things being equal, though, translations tend to put words in similar positions in the verse. When all else fails, it’s worth taking position into account.

- 2. Similarly, even when translations rearrange words, they’ll often keep them in the same sentence. Again, all things being equal, it’s more likely that the same word will appear in the same sentence position across translations.

- 3. If we know that a particular word is in a prepositional phrase, for example, it’s not unlikely that it will serve a similar grammatical role in another translation.

- 4. If words in different translations are both nouns or both verbs, it’s more likely that they’re translating the same word than if one’s a noun and another’s an adverb.

- 5. Here we use the output from the Berkeley Aligner we ran earlier. The aligner is bidirectional, so if we’re comparing the word “Jesus” in one translation with the word “he” in another, we look both at what the Berkeley Aligner says “Jesus” should line up with in one translation and with what “he” should line up with in the other translation. It provides a fuller picture than just going in one direction.

- 6. Here we go more general. Even if the Berkeley Aligner didn’t match up “Jesus” and “he” in the two translations we’re currently looking at, if other translations use “he” and the Aligner successfully aligned them with “Jesus”, we want to take that into account.

- 7. This is similar to grammatical context but looks specifically at dependencies, which describe direct relationships between words. For example, if a word is the subject of a sentence in one translation, it’s likely to be the subject of a sentence in another translation.

- 8. Wordnet similarity looks at the similarities we calculated earlier–words with similar meanings are more likely to reflect the same underlying words.

- 9. This step strips out all words that aren’t nouns, pronouns, adjectives, verbs, and adverbs and compares their sequence–if a different word appears between two identical words across translations, there’s a good chance that it means the same thing.

- 10. Finally, we look at any dependencies between major words; it’s a coarser version of what we did in #7.

- The end result a giant matrix of data–ten vectors for every word-combination in every translation in every verse–and we run our machine-learning algorithm on it, which produces an alignment between every word in every translation.

- At this point, we’ve generated between 50 and 250MB of data for every verse.

- Eighth. Now that we have the direct alignment, we supplement it with indirect alignment data across translations. In other words, to reuse our earlier example, the alignment between two translations may not align “Jesus” and “he,” but alignments in other translations might strongly suggest that the two should be aligned.

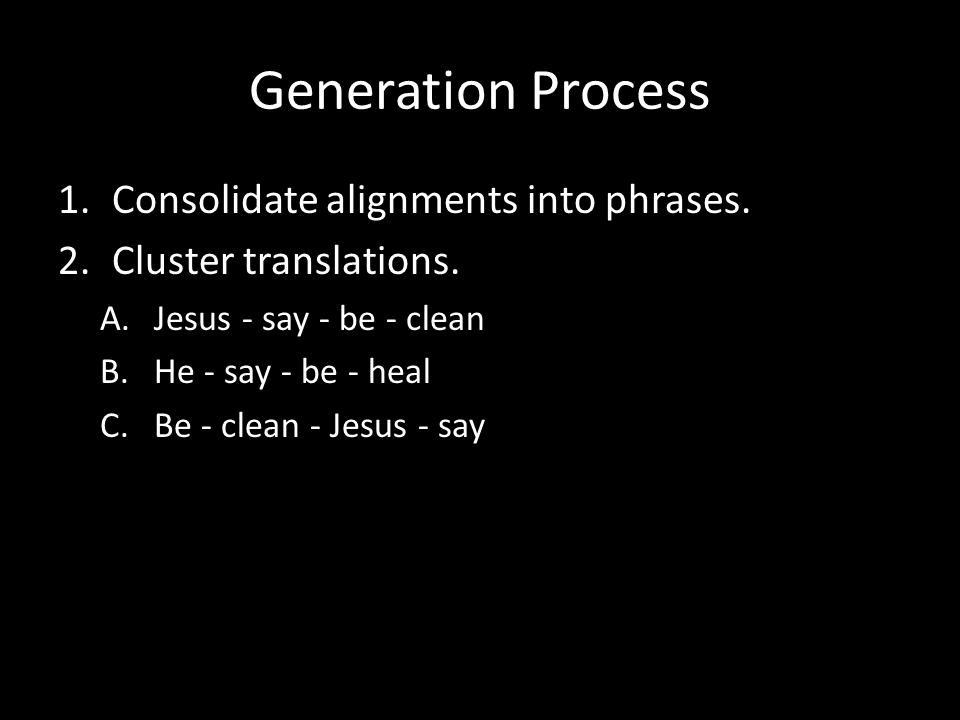

- At this point, we have a reasonable alignment among all the translations. It’s not perfect, but it doesn’t have to be. Now we shift to the second phase: generating a range of possible translations from this data.

- First. Consolidate alignments into phrases, where we look for runs of parallel words. You can see that we’re only looking at lemmas here–dealing with every word creates a lot of noise that doesn’t add much value, so we ignore the less-important words. In this case, the first two have identical phrases even though the words differ slightly, while the third structures the sentence differently.

- Second. Arrange translations into clusters based on how similar they are to each other structurally. In this example, the first two form a cluster, and the the third would be part of a different cluster.

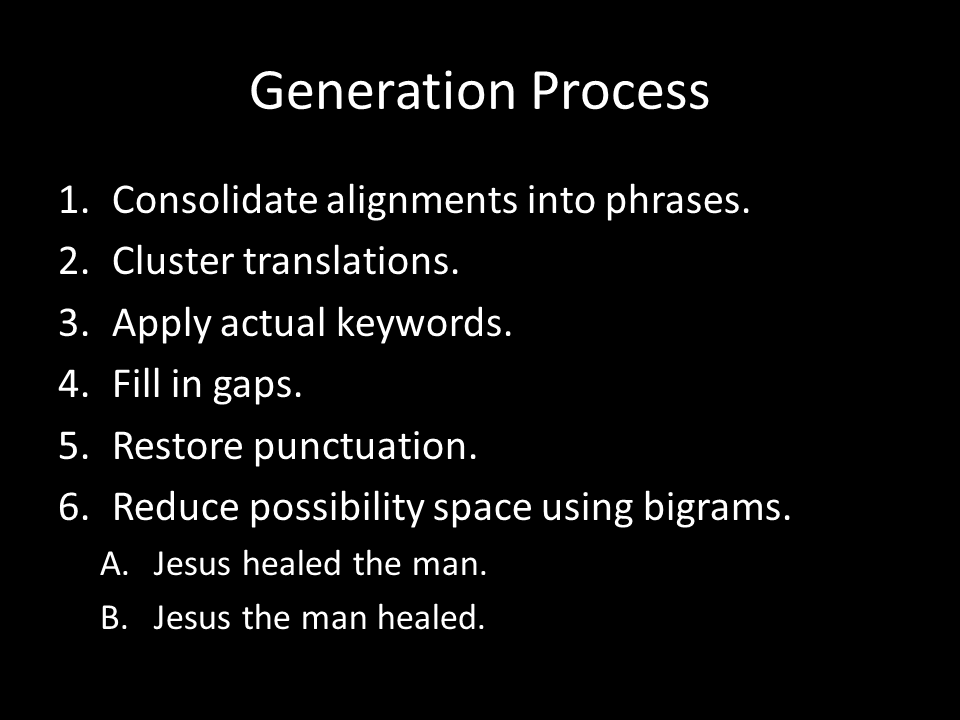

- Third. Insert actual keyword text. I’ve been using words in the examples I’ve been giving, but in the actual program, we use numerical ids assigned to each word. Here we start to introduce actual words.

- Fourth. Fill in the gaps between keywords. We add in small words like conjunctions and prepositions that are key to producing recognizable English.

- Fifth. Add in punctuation. Up to this point, we’ve been focusing on the commonalities among translations. Now we’re starting to focus on differences to produce a polished output.

- Sixth. Reduce the possibility space to accept only valid bigrams. “Bigrams” just means two words in a row. We remove any two-word combinations that, based on our algorithm thus far, look like they should work but don’t. We check each pair of words to see whether they exist anywhere in one of our source translations. If they don’t, we get rid of them.

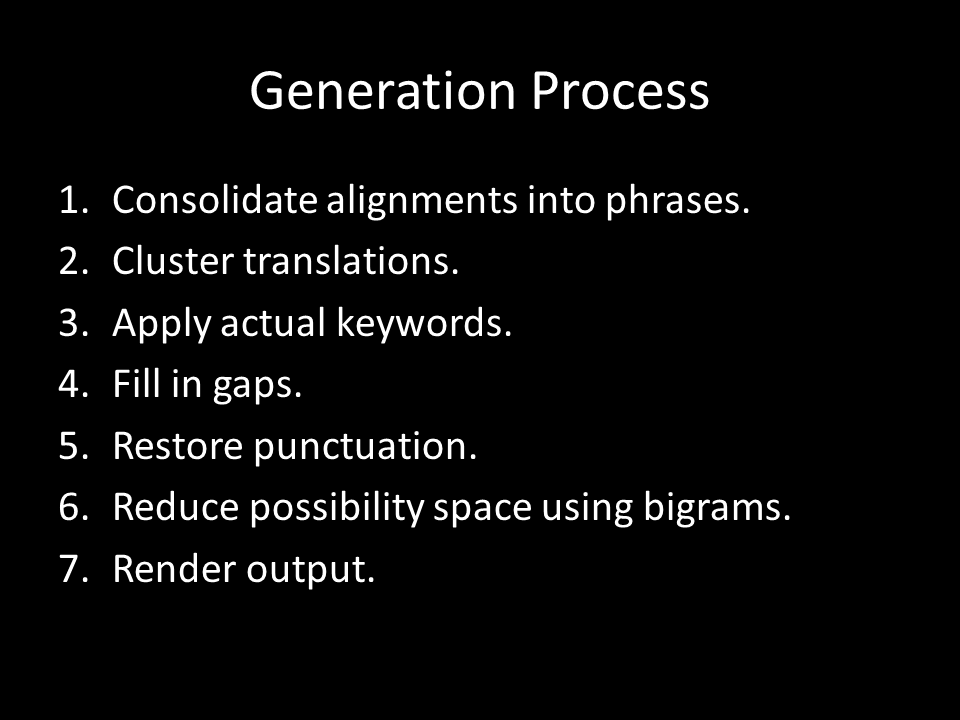

- Seventh. Produce rendered output.

- In this case, the output is just for the Adaptive Bible website. It shows the various translation possibilities for each verse.

- Hovering over a reading shows what the site thinks are valid next words based on what you’re hovering over. (That’s the yellow.)

- You can click a particular reading if you think it’s the best one, and the other readings disappear. Clicking again restores them. (That’s the green.)

- The website shows a single sentence structure that it thinks has the best chance of being valid, but most verses have multiple valid structures that we don’t bother to show here.

- To consider a verse successfully translated, this process has to produce readings supported by two independent translation streams (e.g., having a reading supported only by ESV and RSV doesn’t count because ESV is derived from RSV).

- Using this metric, the process I’ve described produces valid output for 96% of verses in the New Testament.

- On the current version of adaptivebible.com, I use stricter criteria, so only 91% of verses show up.

- Limitations

- Just because a verse passes the test, that doesn’t mean it’s actually grammatical, and it certainly doesn’t mean that every alternative presented within a verse is valid.

- Because we use bigrams for validity, we can get into situations like what you see here, where all these are valid bigrams, but the result (“Jesus said, ‘Be healed,’ Jesus said”) is ridiculous.

- There’s no handling of inter-verse transitions; even if a verse is totally valid, it may not read smoothly into the next verse.

- Since we removed all formatting at the beginning of the process, there’s no formatting.

- Despite those limitations, the process produced a couple of mildly interesting byproducts.

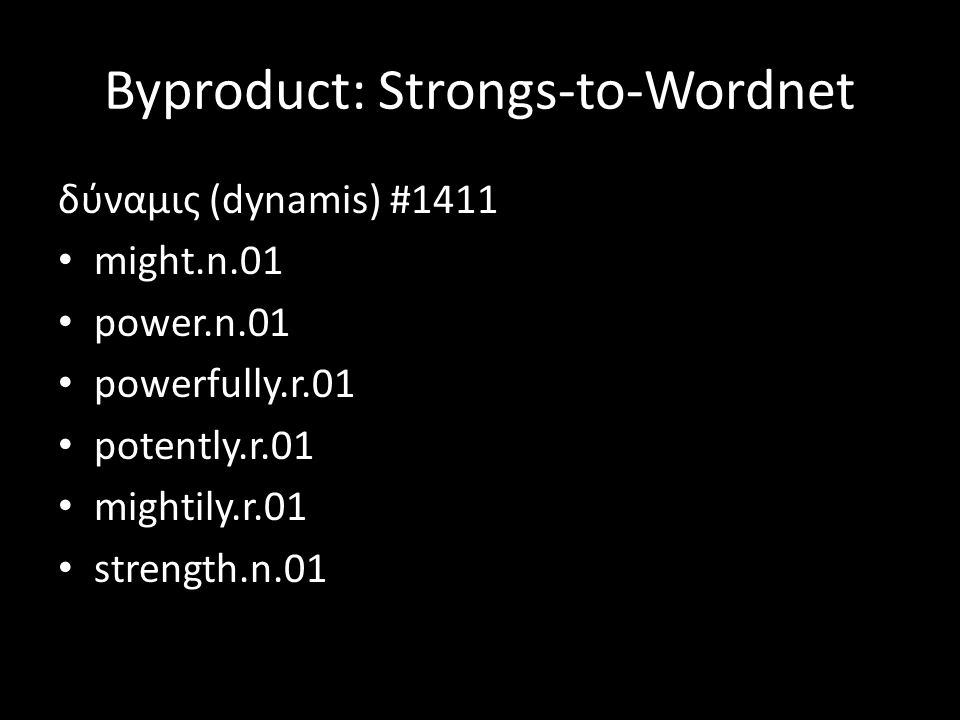

- Probabilistic Strongs-to-Wordnet sense alignment. Given a single Strong’s alignment and a variety of translations, we can explore the semantic range of a Strong’s number. Here we have dunamis. This seems like a reasonably good approximation of its definition in English.

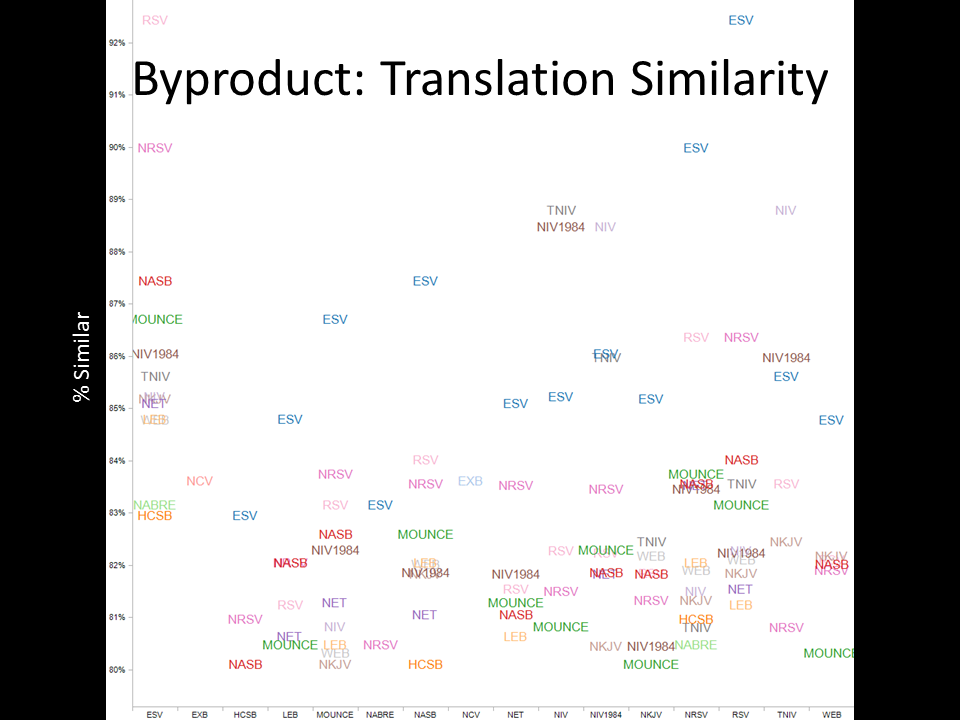

- Identifying translation similarity. This slide explores how structurally similar translations are to each other, based on the phrase clusters we produced. The results are pretty much what I’d expect: translations that are derived from each other tend to be similar to each other.

- What I’ve just described is one pretty basic approach to what I think is inevitable: the explosion of translations into Franken-Bibles as technology gets better. In the future, we won’t be talking about particular translations anymore but rather about trust networks.

- To be clear, I’m not saying that I think this development is a particularly great one for the church, and it’s definitely not good for existing Bible translations. But I do think it’s only a matter of time until Franken-Bibles arrive. At first they’ll be unwieldy and ridiculously bad, but over time they’ll adapt, improve, and will need to be taken seriously.

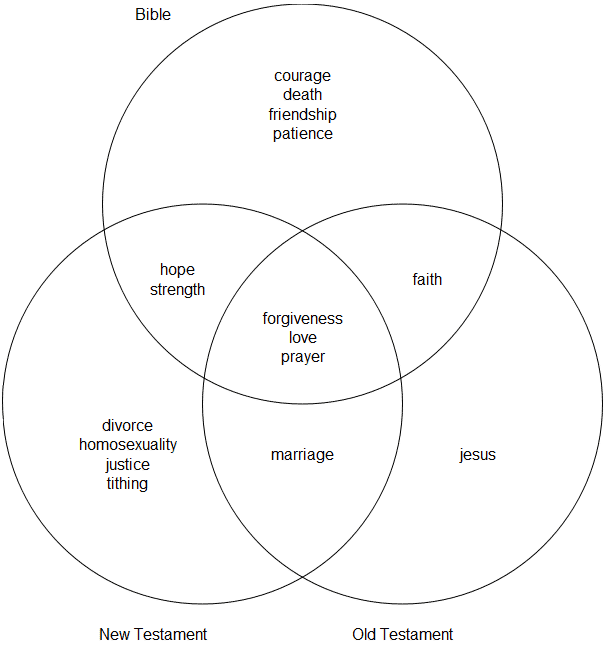

Venn Diagram of Google Bible Searches

Monday, October 25th, 2010Technomancy.org just released a Google Suggest Venn Diagram Generator, where you enter a phrase and three ways to finish it: for example, “(Bible, New Testament, Old Testament) verses on….” It then creates a Venn diagram showing you how Google autocompletes the phrase and where the suggestions overlap.

The below diagram shows the result for “(Bible, New Testament, Old Testament) verses on….” The overlapping words–faith, hope, love, forgiveness, prayer–present a decent (though incomplete) summary of Christianity.

Most Highlighted Bible Passages on Kindle

Thursday, May 20th, 2010Ray Fowler analyzes Amazon’s Kindle data to find the most-highlighted Bible passages on Kindle.

Ten of the fourteen verses overlap the thirty most popular verses on Twitter, a higher percentage than I expected.

Top 100 Linguistic Indicators of Bible-Related Tweets

Sunday, October 25th, 2009When people tweet about Bible verses on Twitter, what words do they use? Here are the top 100:

- bible

- lord

- christ

- gospel

- psalm

- god

- psalms

- corinthians

- preach

- shall

- heaven

- readings

- church

- spirit

- righteous

- verse

- lectionary

- verses

- spiritual

- ministry

- pray

- enemies

- thou

- tongue

- creation

- wisdom

- deuteronomy

- testament

- strength

- refuge

- therefore

- kingdom

- romans

- holy

- thankful

- thy

- reading

- rejoice

- understanding

- faithful

- message

- earth

- blessed

- exodus

- deut

- faith

- wise

- beginning

- pastor

- chapel

- chapter

- survey

- anger

- resurrection

- risen

- read

- hearts

- chronicles

- salvation

- flesh

- servant

- glory

- praying

- kings

- sheep

- praise

- trust

- prosperity

- bless

- heavens

- deeds

- toward

- discussion

- whoever

- speaks

- ye

- hath

- amen

- teaching

- thess

- apostles

- preparing

- eph

- eccl

- path

- fear

- upon

- presence

- inspire

- search

- zechariah

- seek

- teach

- wrath

- commandments

- believers

- humility

- spoke

- thee

- devo

Background

Extracting Bible references from text means identifying whether a given piece of text is referring to a Bible verse or something else. For example, the meaning of Acts 2 depends on context:

- Referring to Bible passage: Acts 2 recounts the early church.

- Not referring to Bible passage: She’s 5 years old but acts 2.

When you encounter a phrase that could be a Bible reference, you have to look at context to determine whether the phrase is a Bible reference. Humans can make this leap pretty easily, but computers need rigorous models and lots of training data to guess whether an ambiguous phrase is a Bible reference. In the above example, the phrase “early church” is a strong indicator that the phrase “Acts 2” is a Bible reference, while the phrase “years old” is an indicator the other way.

Twitter, with its high volume of content and decent search engine, provides lots of training data.

Methodology

Using the Twitter Search API, I downloaded 30,000 tweets possibly containing Bible references (e.g., [john 3], [jeremiah 29]) and then categorized them by hand as referring to a Bible verse or not.

I then ran a Naive Bayes algorithm on the resulting tweets to produce the above list, which contains the words that most strongly indicate the presence of a Bible reference.

This list suffers from sample bias, of course: a different set of tweets would produce a different list. In addition, the list is Twitter-centric; the results may not carry over into blogs or other media. (People substitute the number “2” for the word “to” and “4” for “for” on Twitter more frequently than they do elsewhere, for example, which oversamples content like “I’m meeting Matthew 4 dinner.”)

See It in Action

Search for Bible references on Twitter. Use the relevant and not relevant buttons to improve the filtering. I haven’t formally announced this new feature of OpenBible.info yet; consider the link a preview.

750 Memory Verses for You

Wednesday, May 13th, 2009Download 750 verses (or short combination of verses) for your memory work or as the basis for your own list of verses. The Bible text in the file is the ESV and is therefore copyrighted, but the compilation of actual verse references is available under the usual (for OpenBible.info) CC-BY license. Do what you like with them.

The verses appear in descending order of popularity (as determined by an analysis of verses on this site), so if you’re only looking for 100 verses, you can just grab the first 100. There are 750 total to give you more than two years’ worth of daily verses, if you want.

Background

When I was putting together a list of daily memory verses a few years ago, I was surprised to discover that I couldn’t find a freely usable list of verses: I ended up combing through a bunch of books and combining various sources to produce a list of about 400 verses. If you’re doing something similar, why should you go through the same pain?

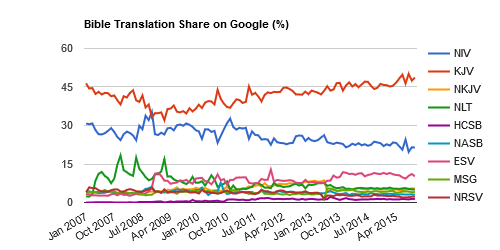

New Feature: Bible Translation Googleshare

Sunday, November 30th, 2008New from the OpenBible Labs: a chart that tracks the popularity of English Bible translations (click for a larger version):

The goal is to see how well this kind of data tracks official marketshare figures. Unfortunately, I’m not aware of any publicly available marketshare figures. (If anyone knows of any, feel free to leave a link in the comments.) In principle, this chart should provide a leading indicator of sales—if you accept the idea that mindshare precedes sales.

The result more-or-less tracks the CBA Bible Bestseller List (pdf), with a couple of exceptions. The chart appears to undercount the NKJV and the HCSB, which means that either (1) there’s a data problem—for example, some NKJV results may appear as part of the KJV data; or (2) these translations’ sales in CBA bookstores overstate their prominence as translations—in other words, they sell well in CBA bookstores, but people tend not to search for them much in Google. I lean toward the first answer: it’s likely that my methodology is flawed somehow.

Technical Background

The chart blends data from Google Trends and the Google Keyword Tool to see how many searches people conduct for various English Bible translations. Data before July 2008 is from Google Trends exclusively, while more recent months include data using the methodology described in Bible Translation Mindshare.

Originally, I wanted to use only this latter methodology. However, the data is chaotic; the figures jump around quite a bit, and the Google Keyword Tool sometimes gives inconsistent results even for the same search in the same month. For this reason, I decided to smooth the data a bit with Google Trends, which provides more consistent data from month to month.

Finally, I should mention that I have lots of potential conflicts of interest in producing this data.

Bible Translation Mindshare in Google

Saturday, July 12th, 2008Google recently updated its AdWords Keyword Tool, showing you, for the first time, the approximate number of searches for a keyword in a given month.

I thought I’d see how many people search for various Bible translations. The results:

| Version | Queries | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| KJV | 591,684 | 42.0% |

| NIV | 436,000 | 30.9% |

| NLT | 159,100 | 11.3% |

| NKJV | 87,880 | 6.2% |

| NASB | 54,540 | 3.9% |

| ESV | 34,569 | 2.5% |

| MSG | 30,900 | 2.2% |

| TNIV | 10,500 | 0.7% |

| HCSB | 4,425 | 0.3% |

Translations

The translations come from the CBA Bible Translation Bestseller List. (CBA is the Christian Booksellers Association, a Christian-retailing industry group.) This list counts Bible sales through most Christian bookstores in the US. However, it’s an imperfect measure of a translation’s popularity since sales through non-CBA stores are becoming more important to Bible publishers.

The imperfection of the CBA list (and the desire to quantify its rankings) was the inspiration for this (also-imperfect) project.

Methodology

Bible version abbreviations that also have other meanings were a little tricky. “HCSB” is also the name of a bank and a school board in Florida. “ESV” is also a Cadillac and the stock symbol for an oil-drilling company. To compensate for these other uses, I took the top three non-Bible keyword phrases and compared the numbers for the top-three Bible related keyword phrases.

For example, there were 90,500 searches for “esv” in June. The keywords “escalade esv,” “cadillac esv,” and “cadillac escalade esv” had 57,300 searches, while “esv bible,” “esv online,” and “esv study bible” had 13,300 searches. Multiplying 90,500 by 19% (the proportion of the top three Bible-related searches to the top three non-Bible-related searches) leads to the conclusion that about 17,049 of those 90,500 searches for “esv” were Bible-related. It’s definitely an approximation, but the alternative was to count acronym-only searches for some translations and not for others.

Besides the ESV and HCSB, other Bible-translation acronyms have a few other meanings, but they don’t suffer from nearly the level of acronym confusion as those two translations. The HCSB also goes by the name “CSB,” which makes things even harder. Nothing Bible-related showed up when I entered CSB into the keyword tool, so I didn’t count it.

A similar problem occurs for the phrase “king james”—with 301,000 searches in June, it was the single most-popular translation-related query. But are the searches for the Bible translation or for, say, King James I of England? Based on the popularity of the related keywords, it looks like 97% of “king james” searches are for the Bible. This query puts the KJV well ahead of the NIV in popularity.

The Message also probably suffers from undercounting, since it’s impossible to know how many people searching for “message” are looking for the Bible (not too many, based on the Keyword Tool’s data—but definitely some).

Here are the words and phrases I started with. I included other clearly relevant synonyms in the total.

- christian standard bible

- english standard version

- esv bible

- esv bibles

- esv translation

- hcsb bible

- hcsb bibles

- hcsb translation

- kjv

- kjv bible

- kjv bibles

- kjv translation

- message bible

- message bibles

- message translation

- msg bible

- msg bibles

- nasb

- nasb bible

- nasb bibles

- nasb translation

- new american standard

- new international version

- new king james

- new living translation

- niv

- niv bible

- niv bibles

- niv translation

- nkjv

- nkjv bible

- nkjv bibles

- nkjv translation

- nlt

- nlt bible

- nlt bibles

- nlt translation

- tniv

- tniv bible

- tniv bibles

- tniv translation

Practical Biblical Collective Intelligence

Tuesday, May 20th, 2008Sean at Blogos recently wrote about applying collective intelligence to biblical studies. His post leads me to write about an experiment I’ve been running even though the experiment isn’t quite fully baked yet.

Collective intelligence (sometimes called “the wisdom of crowds”) is something that I think will become more important in biblical studies as it becomes more important in other disciplines. The vast scope of the Internet makes possible explorations of questions that have been impractical until now.

So, what’s a practical application of collective intelligence to biblical studies? Paragraph and section identification to help people study the Bible.

I paid 40 people on Amazon’s Mechanical Turk two cents each to add paragraphs to the book of Philemon in both the ESV and NLT translations. Total cost (including commission): $1.00.

Results

The thickness of the bar in the below table indicates how many people would start a paragraph at the given sentence. The ¶ symbols (not sent to the Turkers) indicate where the Bible translators themselves started paragraphs.

The table shows similarities between the two translations (except for some variation near the beginning) and also reveals some divergence with the translators’ paragraph ideas.

(If you’re reading this post in a feed reader, the below table won’t make much sense to you. You should click through to the original post if you want to see the styles.)

| Philemon (ESV) | Philemon (NLT) |

|---|---|

| ¶ Paul, a prisoner for Christ Jesus, and Timothy our brother, | ¶ This letter is from Paul, a prisoner for preaching the Good News about Christ Jesus, and from our brother Timothy. |

| ¶ To Philemon our beloved fellow worker and Apphia our sister and Archippus our fellow soldier, and the church in your house: | ¶ I am writing to Philemon, our beloved co-worker, and to our sister Apphia, and to our fellow soldier Archippus, and to the church that meets in your house. |

| ¶ Grace to you and peace from God our Father and the Lord Jesus Christ. | ¶ May God our Father and the Lord Jesus Christ give you grace and peace. |

| ¶ I thank my God always when I remember you in my prayers, because I hear of your love and of the faith that you have toward the Lord Jesus and for all the saints, and I pray that the sharing of your faith may become effective for the full knowledge of every good thing that is in us for the sake of Christ. | ¶ I always thank my God when I pray for you, Philemon, because I keep hearing about your faith in the Lord Jesus and your love for all of God’s people. |

| And I am praying that you will put into action the generosity that comes from your faith as you understand and experience all the good things we have in Christ. | |

| For I have derived much joy and comfort from your love…, because the hearts of the saints have been refreshed through you. | Your love has given me much joy and comfort…, for your kindness has often refreshed the hearts of God’s people. |

| ¶ Accordingly, though I am bold enough in Christ to command you to do what is required, yet for love’s sake I prefer to appeal to you—I, Paul, an old man and now a prisoner also for Christ Jesus—I appeal to you for my child, Onesimus, whose father I became in my imprisonment. | ¶ That is why I am boldly asking a favor of you. |

| I could demand it in the name of Christ because it is the right thing for you to do. | |

| But because of our love, I prefer simply to ask you. | |

| Consider this as a request from me—Paul, an old man and now also a prisoner for the sake of Christ Jesus. | |

| ¶ I appeal to you to show kindness to my child, Onesimus. | |

| I became his father in the faith while here in prison. | |

| (Formerly he was useless to you, but now he is indeed useful to you and to me.) | Onesimus hasn’t been of much use to you in the past, but now he is very useful to both of us. |

| I am sending him back to you, sending my very heart. | I am sending him back to you, and with him comes my own heart. |

| I would have been glad to keep him with me, in order that he might serve me on your behalf during my imprisonment for the gospel, but I preferred to do nothing without your consent in order that your goodness might not be by compulsion but of your own accord. | ¶ I wanted to keep him here with me while I am in these chains for preaching the Good News, and he would have helped me on your behalf. |

| But I didn’t want to do anything without your consent. | |

| I wanted you to help because you were willing, not because you were forced. | |

| For this perhaps is why he was parted from you for a while, that you might have him back forever, no longer as a slave but more than a slave, as a beloved brother—especially to me, but how much more to you, both in the flesh and in the Lord. | It seems you lost Onesimus for a little while so that you could have him back forever. |

| He is no longer like a slave to you. | |

| He is more than a slave, for he is a beloved brother, especially to me. | |

| Now he will mean much more to you, both as a man and as a brother in the Lord. | |

| ¶ So if you consider me your partner, receive him as you would receive me. | ¶ So if you consider me your partner, welcome him as you would welcome me. |

| If he has wronged you at all, or owes you anything, charge that to my account. | If he has wronged you in any way or owes you anything, charge it to me. |

| I, Paul, write this with my own hand: I will repay it—to say nothing of your owing me even your own self. | I, Paul, write this with my own hand: I will repay it. |

| And I won’t mention that you owe me your very soul! | |

| Yes, brother, I want some benefit from you in the Lord. | ¶ Yes, my brother, please do me this favor for the Lord’s sake. |

| Refresh my heart in Christ. | Give me this encouragement in Christ. |

| ¶ Confident of your obedience, I write to you, knowing that you will do even more than I say. | ¶ I am confident as I write this letter that you will do what I ask and even more! |

| At the same time, prepare a guest room for me, for I am hoping that through your prayers I will be graciously given to you. | One more thing—please prepare a guest room for me, for I am hoping that God will answer your prayers and let me return to you soon. |

| ¶ Epaphras, my fellow prisoner in Christ Jesus, sends greetings to you, and so do Mark, Aristarchus, Demas, and Luke, my fellow workers. | ¶ Epaphras, my fellow prisoner in Christ Jesus, sends you his greetings. |

| So do Mark, Aristarchus, Demas, and Luke, my co-workers. | |

| ¶ The grace of the Lord Jesus Christ be with your spirit. | ¶ May the grace of the Lord Jesus Christ be with your spirit. |

Let’s take this approach one step further, asking people to group the paragraphs into sections (pericopes), titling those sections, and then having other people vote on which section titles are best. Unfortunately, this part of the experiment is still in-process, so I don’t have anything interesting to show you.

Practical Implications for Bible Software

Purveyors of Bible software are in a unique position to benefit from this kind of collective intelligence. Although they don’t have the massive volume of users found on the Internet, they data they compile from Bible software users will be of higher quality than data compiled from the Internet. (For one, Bible software users probably aren’t out to attack Christianity, unlike a good number of people on the Internet.)

Further, Bible software publishers can create tools to implicitly shape collective intelligence to their users’ benefit. For example, they could create a tool that allows people to add their own paragraphs and sections to Bible texts. This tool could let you share this data you create anonymously with other users of the software. The goal isn’t to create the “one true paragraph and section divisions” for a passage, but merely to inform people of the choices others have made, indicating (if someone desires) how other people organize biblical texts.

Similarly, Bible software could help people anonymously share outlines of Bible books. I think you could also rank relevant resources (commentaries, say) for certain passages based on the resources people consult after reading those passages and the length of time they spend looking at the resources.

The idea behind this kind of collective intelligence is to collect implicit data—data based on things people are already doing—to improve the software. The more people who use the software, the better it becomes. You could try to come up with a slick algorithm to predict, say, the most relevant resources for a passage. But the beauty of a collective-intelligence approach is that the abundance of data means that even a simple ranking algorithm produces good results. Or, as Anand Rajaraman puts it, “more data usually beats better algorithms.”

I’m excited about applying collective intelligence to biblical studies. Implicit-data aggregation provides the most promising short-term possibilities, since a lot of data regarding user behavior in Bible software already exists. Pragmatically, I think Bible software publishers can get a lot of mileage just by analyzing this data and allowing it to inform their interface in limited ways.

But explicit collective-intelligence projects, such as the parable finder that Sean discusses in his post, could bear fruit in the long run. The key is to get lots of data—even noisy data will do—that can serve as the basis for analysis.